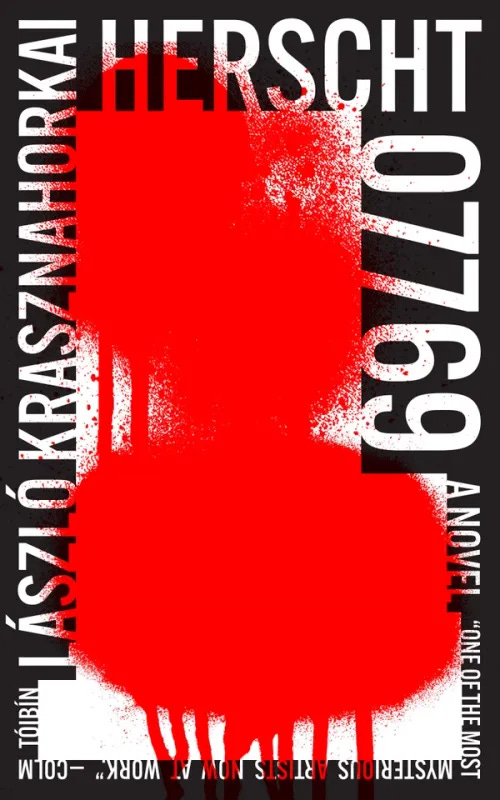

Herscht 07769, by László Krasznahorkai (published today, September 3, 2024, by New Directions; translated from the Hungarian by Ottilie Mulzet), is ostensibly about three things: Thuringian neo-Nazis, speculative particle physics, and the ontological status of the music of Johann Sebastian Bach.

Also present, for those already familiar with his work, are all the indicators of a good Krasznahorkai novel: provincial uneasiness, a solipsistic feeling of imminent doom, a protagonist with his head in the clouds (with all the attendant visions of melancholic sweetness), personal fixation, petty paranoia, mobs, packs, crowds, eerie misgivings; I could go on: distrust, muttering and rumors, portent. The book is steeped in an atmosphere of fear reminiscent of War and War (of which James Wood said: “[T]his is one of the most profoundly unsettling experiences I have had as a reader.”), even though the setting reminds one much more of Baron Wenckheim’s Homecoming or The Melancholy of Resistance (all three published, respectively, by New Directions in 2006, 2019 and 2000).

Herscht 07769 begins as Florian Herscht, a giant, simpleminded and sweet man, beloved by all in the small Thuringian town of Kana, mails a letter of concern to German chancellor Angela Merkel, specifically about what Florian understands to be the imminent (and immanent) possibility that a surplus antimatter particle will arise in the constant subatomic dance of matter and antimatter, resulting in the disappearance of all reality. The cast of characters is familiar: old women, workers, drinking packs of men in the bar, gas station attendants—and one of them, Herr Kӧhler, has taught Florian such things as compel him to his own apocalyptic conclusions (which Herr Kӧhler seems not to take seriously, though his actions suggest otherwise).

To sidestep a little: There is a minor character, Auntie Ingrid, who is not, at first glance, the conceptual locus around which Herscht 07769 revolves. She is a dotty old woman who can only seem to talk about a projected flower show or flower contest that she has thought up, the Chrysanthemum Competition, amidst and seemingly despite the continually mounting tensions of the town. She accosts anybody unfortunate enough to come close to her with a recounting of the idea for the competition, all the people who have already signed up to participate, and so on, going so far as to ring every doorbell in the small town to get more signatures. When residents stop answering their doors, she expresses her surprise that so many could have let their doorbells stop working simultaneously(!).

The three ostensible subjects of the novel, mentioned above, are somewhat more advanced than Auntie Ingrid’s prospective flower show—but each of them nevertheless functions in exactly the same way for their respective adherents: a neo-Nazi gang holds its members and the townspeople alike in thrall, particle physics becomes the “gentle giant” Florian Herscht’s main concern for almost half of the book, and Bach, or the image of Bach and his music as a Teutonic pseudo-symbol, is the metric against which the Boss (the gentle giant’s neo-Nazi benefactor) measures all. These spheres of obsession hang over the heads of the people of Kana like personal macrocosms (sic) into which they stick their heads, believing themselves to have the whole cosmos in front of them like sad inversions of the famous Flammarion engraving, in which a Giordano Bruno-like figure peeks through a break in the fabric of the firmament at the higher spheres. Florian is the only character who is able to remove his head from his false macrocosm.

In a sense, Florian is not an Idiot–like protagonist because he has his head in the clouds; he is the supreme idiot (and consequently the hero–protagonist) precisely because he is the only character who is able to remove his head from those very clouds (or see over them). All others “end up,” to generalize, with their heads firmly ensconced in clouds—to reiterate—of intensely solipsistic manufacture.

Again, that is what makes Florian the main character and everybody else an Auntie Ingrid—and although she is admittedly the most pathetic possible cipher with which to read the characters of the book, she is nevertheless very human and sympathetic.

Krasznahorkai’s characters can, at times, seem far-away and small, but they are never flat. They are always terribly human, not unlike the distant figures in a Bruegel painting, each going about in his or her own way in the world at large. This Bruegel quality reaches an alarming degree of sharpness in Herscht 07769.

Through the constellation of confused obsessions belonging to the characters in Herscht 07769—the monologic explications of which take up vast swathes of discontinuous narration—there runs a sense-pole, a theme, of something like the possibility of redemption. This is the core of the book. At the top of this sense pole, or thematic axis, is the actual music of Bach, rather than the national myth–idea of him, and at the bottom of the axis there is animality. Music and animality: the most beautiful stretches of Krasznahorkai’s single-sentence composition inhabit these two subjects, and readers familiar with his other work, particularly Seiobo There Below (New Directions, 2014), will hear these as variations on a deep theme.

The polar concepts of music and animality combine in the protagonist Florian Herscht to amazing effect. The first half of the book, bleak realism notwithstanding, has something farcical—almost funny—about it: Florian has been taken under the wing of the hard-talking, swearing, tattooed, weight-lifting man referred to as the Boss, who also happens to be Florian’s actual boss in a graffiti clean up crew, and, further, the head of a local neo-Nazi gang. Nothing about this is necessarily funny, not until the Sancho Panza–like sensibilities of Florian (an explicitly “half-witted,” universally loved man) come into play, turning the Boss, by default, into a kind of perverse, neo-Nazi–Don Quixote stand-in. The comparison may seem tasteless, but it fits—only up to a certain point, for these characters are not types by any means. In word and act, they are quite singular.

But the second half of the book changes key drastically—I briefly second-guessed whether I had been reading with a bad ear for the first 200 pages—a change that comes about when Florian finally begins to listen to Bach, rather than to the Boss, who only goes on about Bach, the German national spirit, and so on. The music of Bach radically disconnects our hero, hitherto a tragi-comedic Sancho Panza, from the crass demands and constraints of his immediate world (which his previous obsession with particle physics accelerated to the point of mania in the beginning of the book, leading to the bizarre though touching series of letters written and sent off to Angela Merkel). The possibility of laughter, which earlier reared its farcical face, falls away entirely. The book becomes very serious. It is only once this break occurs in Florian that he really becomes who he is: the feared wolf man of the middle ages, living on the outskirts of society, whose actions are guaranteed by no law and who must steal food and wander in the wilderness to stay alive. He has more in common with the animals of the Thuringian forest (represented variously by a deer which meets him calmly, dogs that do not bark at him and most starkly by the ominous wolves and wolf-imagery throughout the book, and, toward the end, by an eagle that follows him) than with people.

Herscht 07769 begins as a disconcerting and strange farce and ends as a dark, absolutely beautiful fable, one identifiable moral of which seems to be something like the following: that goodness (Florian) is precisely what the bad (the Boss) uses to protect and empower itself, and that to stop what is actively bad, mere goodness is not enough and must undergo a radical shift, which in the case of this book hinges on the violence and beauty of both animality and music, or—to compress these into a single word—sublimity.

Thank you to Madeleine Nephew and the publicity department at New Directions for the galley edition.