This third, silent interlocutor, the reader (INTERR-COM’s FBI caseworker or censor from the Goskomizdat of the mind), gets included in the discourse, a shoddy stand-in for some kind big Other. In this way, the reader (like a censor) signs their name to everything we say here.

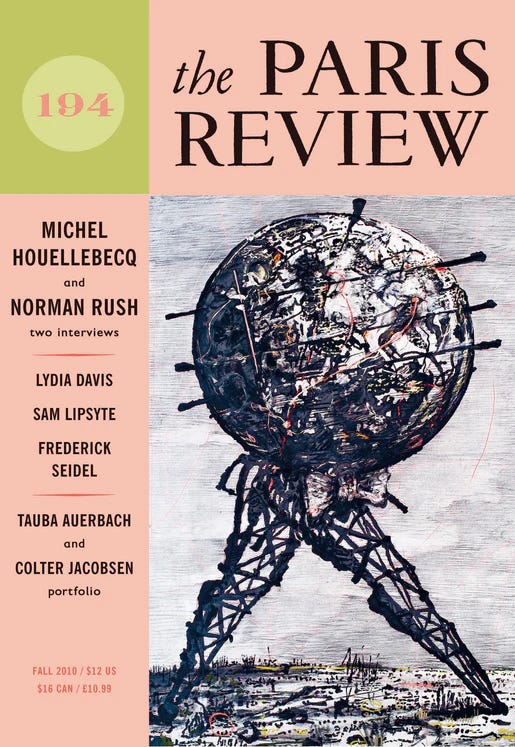

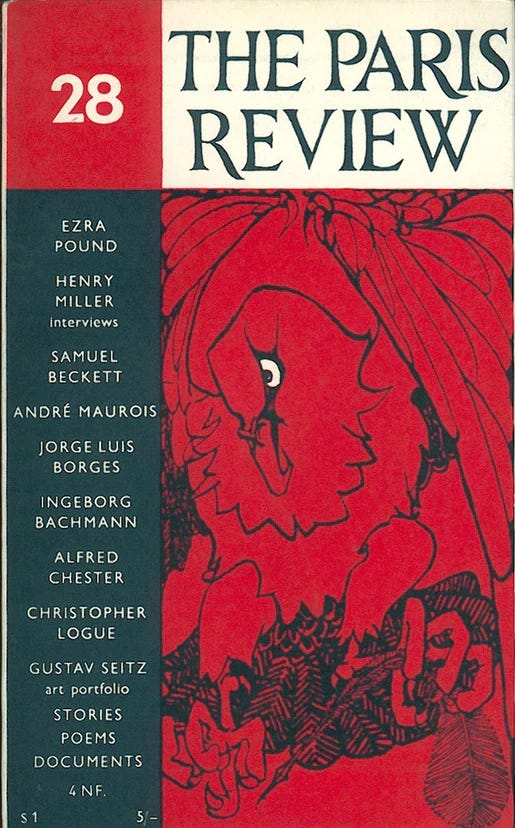

I’m not a journalist, and this isn’t The Paris Review, so why would I want to interview anyone? I feel compelled to read and to write, and when you interview someone, you’re doing those two things in half-measure, or half-consciously; you’re doing them together, and the other person, the interviewee, does them back. And if you’ve never really done it before, it’s like conducting an experiment without any kind of sound hypothesis, which means you’re not doing it to prove anything—which is the purest kind of experiment and therefore very much worth doing.

I first thought of INTERR-COM (you might notice the two Rs and that there aren’t two Rs in the word “interview”) one night sometime around last Christmas. I was reading Ghosts of My Life, and the interview sections reminded me of how much I used to like reading “The Art of Fiction” in The Paris Review. A friend of mine would also read them, and we would discuss the interviews together. We were probably 13 or 14. They were fun, they felt instructive, not so much in an informational way but in a temperamental or “spiritual” way, and we didn’t need to know who the writers were to enjoy what they said. Often, it was better that we didn’t know who they were, what they looked like or whether they were even alive still.

I can’t help but look back on one of the very first pieces on COM-POSIT, where I explicitly talk shit about interviews.

The greatest orators are mediocre writers, and when the writer starts telling a story to a handful of listeners, even if these are sympathetic friends, he goes along as if over a narrow, exposed bridge crossing a flowing moat of everything in him that is insufferable.

[…]

Writers should be, above all, observers and listeners, which is why hearing them speak—especially of their own work—is often repellent

But this is basically my caveat:

We don’t know how to speak with the economy of the hand: the voice is necessarily overwhelming.

I suppose I was talking about a certain kind of spoken/recorded “literary” interview, not really so much the written kind, which I am able to like (and often enough, spoken interviews are fine too…). When two initials are writing back and forth, you never have to hear their literal voices.

Writing back and forth with someone and calling it an interview—that works, it’s a dialogue in the interrogative key, a game wherein one person pushes the pedals and the other steers. The destination cannot be predetermined but is created in the doing, improvised right at the end. It is like an exchange of short letters wherein the two writers are fully aware that the censor is reading everything they write—but who also don’t mind. Maybe this censor is even a sympathetic “man on the inside.” This third, silent interlocutor, the reader (INTERR-COM’s FBI caseworker or censor from the Goskomizdat of the mind), gets included in the discourse, a shoddy stand-in for some kind big Other. In this way, the reader (like a censor) signs their name to everything we say here.

At the time I had the idea for INTERR-COM, I was also reading some of A Thousand Plateaus (inspired, in part, by Henry Miller and Michael Fraenkel’s Hamlet Letters, which I kept in mind) and wondered how it would be to write with someone else on and along the same plane—even if we were marked out by initials.

In that spirit, I will reserve INTERR-COM for collaborative works as well, in the broadest sense: profiles, interviews, exchanges, botched editorials, direct interrogations, co-authored pamphlets, plays, theses, confessions, translations, forgeries and whatever else.

Maybe I’ll even open it up for submissions or proposals one day.

So far, interviews have been fun, although I will admit that, at first, even the low-stress way in which I conducted things was slightly distressing. I felt as if I were taking responsibility for what someone else said before they said it—before I even “interviewed” the person! But that’s not really how it is, not at all. Everything speaks for itself, none of it needs to be fully explained.

I have no idea what the schedule for INTERR-COM is going to be. I could do three per year or one every two months.

If you have not yet read the first installment, I highly recommend it. As far as firsts go, this one couldn’t have been better. Billy Pedlow can really put a sentence together—not to mention a fantastic book of poetry.

Billy Pedlow, INTERR-COM No. 1

"In both my paintings and poems you have characters trapped in performances of cruelty, debasement, and yearning. That’s what I am interested in."