Some Things about Ficino

A Subversion

An Arrest

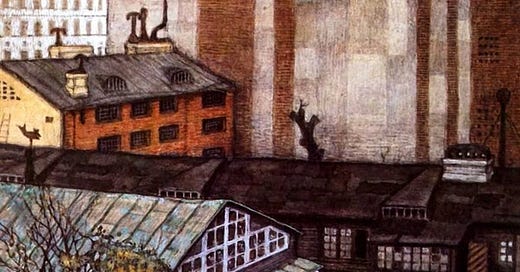

Night had just begun to fall, and the last train pulled away from the station into a distance of dark trees. From the other side of the street, across from the open platform, Ficino, a middle-aged man of middle height with thin, brown hair and blue eyes, watched the lights get smaller, recede, and disappear. The heavy sound of the train against the tracks hung in the air like a flare and faded, faded, and was cut by blows from the horn, until all that could be heard was the backward rushing of the trees in the wind. So he would not be going home tonight. Ficino stood there for a moment, feeling the weight of his black duffel bag on his shoulder. The wind descended lightly from the treetops and pushed his hair across his head, like fine silica being blown across a smooth desert. To his left lay the small town wherein he had just spent several days giving talks at the university—ostensibly from a philological position—on insurgency (L. insurgentum: Obs. Fr. insurger, “to rise in opposition,” and so on.), and to his right lay a street, just a street, with houses lining it, that disappeared into the distance like the train had, and yet differently, for the street did not move, but disappeared somehow nonetheless. There was a cafe built snuggly into the station, across the street from where Ficino stood. It was like the rear of a cathedral, low, with a circling glass rooftop (the chancel and ambulatory—the part of the structure that had to do with passengers and ticketing would have been like the nave and the transept). Through the cafe’s dim, warmly lit windows, he could see the glittering colors of glass bottles, a white scythe of reflection on a coffee pot, its red switch glowing, and the warped, partial reflections of the houses behind him. The waiter was outside, smoking in the red light of the railroad signals. Inside, the bartender leaned, taking sips from a white mug. Ficino crossed the street and went in, found a seat near the street-facing windows, slipped the big duffel bag discreetly into the space between the table legs and the low wall, and sat. The waiter hurriedly put out his cigarette and jogged inside. Ficino ordered beer. Beer was brought, and Ficino tilted his chair back on two legs. The bitter, cold taste of it was tonic and vivifying. He drank it down and ordered another. Still tilted back on two chair legs (to the backgrounded bartender’s intense consternation), Ficino marveled at the sweeping aspect of the cafe’s windows. It was a theater of fractured but smooth light and color, behaving, visually, like mercury. It was totally dark out now, and the stars shone down through the glass one by one, like far away, flickering candles, and the moon even showed itself, though only as a reflection of a reflection, the geometry of which Ficino couldn’t easily trace, for he was facing west and the white hologram of its image hovered somewhere to the northwest. Ficino drank, and soon he was thinking of his work, estimating how the talks had gone—this one had been listened to with the utmost attention, that one left his audience mumbling; a listener had been making notes on a pad, and so on, in desultory fashion—and then he remembered something that had happened on the second to last night. How had he not thought of it again since? Tipped far back on the legs of the chair, he went over the events, taking short, frequent sips of the golden beer, his blue eyes glazing over as they stared through the false star map of the cafe windows spread out before him. At the classroom lectern, Ficino had paused, not for effect, which was taking its natural course through a handful of listeners, but to quickly glance over the program of the next day’s lecture. He spoke again, breaking the light tension that had built from his conclusion (an etymological conclusion, cut and dry and fairly uninteresting actually, but that seemed to endorse the course of the word, his subject, its untroubled movement through lexical fields, that seemed to encourage its own untroubled meaning, happily separate from all fraught history below it, like a soft breath upon an ember, that winked sideways without irony, with gentleness, that played coy in all seriousness and said “Here stands this word.”) “Tomorrow, we'll leave the subject of insurgency. The title, as you can see—.” He turned back to the crowd and noticed, standing beside the wide lecture hall doors, two men in blue flight suits. One was hopping up and down with his hands in his pockets, like a kid who has to use the bathroom, and the other was taking notes on a legal pad attached to a clipboard. Ficino saw that they looked exactly the same, meaning that they looked like identical twins, except the one writing was wearing black-framed glasses and the one hopping around anxiously had noticeably blonder hair than the more serious-looking one. Ficino dismissed the class and gave a friendly wave to the students already standing from their seats. The doors opened. Ficino stacked his papers, read over a few lines, crossed out some in red ink and made fresh notes above them in blue. But he glanced up (not over the rim of a pair of glasses—don’t imagine it that way, just because he was a lecturer at a podium with some papers shuffling around in his hands, but remember, his eyes were blue and his sight was very good, so he had no need to go on peeking over the rim of a pair of glasses like a sniveling academic or old librarian, he just looked straight up with his whole head, guided by his eyes, which were wide open, unsquinting, etc., and his posture followed the lead of this look, so that when he looked, he looked with his whole body, as though with his chest, but also with his eyes, unmediated by glasses—one can’t stress that enough—he could see just fine) and looked at the two men in the blue flight suits, the one still writing, the other pacing left and right in an almost ridiculous manner, his arms swinging every which way. Well, it seemed weird to Ficino, so he put his papers down (don’t imagine him taking his glasses off, like a pugilist taking off his gloves to fight dirty, because he didn’t even wear glasses, he didn’t need them, etc., and so you should see him as he was, shoulders squared and unhunched, clear-eyed, unbothered, nothing funny about him, hands relaxed in his pockets like a regular, unremarkable, oh but very normal guy) and walked down into the pit of the lecture hall. But before he could even reach the aisles that led back up toward where the two men were standing, they froze, like burglars caught in a spotlight, eyes as big as silver dollars, stared at Ficino walking up toward them, the lecturer’s head cocked slightly to one side in a friendly, approachable and approaching manner, and the men darted out of the door in a flurry of rustling notebook paper and swishing, flight suit, leg-on-leg running sounds.

“Some Things about Ficino”, first published by Punt Volat, 2024.