Turning off all but one lamp in the somewhat remote house where me and my girlfriend are staying for the Winter, I have decided to pick up the first volume of my favorite book. It’s a newer translation that I have wanted to read for years but which I have not acquired until recently, so dedicated do I feel to my three silver and black volumes of Remembrance of Things Past by Marcel Proust, translated by C.K. Scott Moncrieff.

I’m sitting in the kitchen, and outside I can already see the beginning of a snowstorm, quietly exposed, like a mime alone at the center of a stage, in the white beam of the streetlight.

Sometimes, when I reach the end of a book, I tear up. Traversing the last paragraph, my emotion has less to do with the text than with the pale cliffside of its end, the final period and the moment in every book when you look up and realize that the voice you were hearing for so long has already gone.

Emotion rises at the approach of the end. But this is the only book that has also made my eyes well up at its beginning.

Reading this relatively new translation, In Search of Lost Time, I realize that this book, so steeped in the mysteries and aether of memory, was never itself a memory for me, a recollection of my own, when I first read it. But now, even these opening pages where Swann quietly comes into the family home at Combray, where the aunts chat back and forth, where the narrator’s grandmother wanders the garden paths in the rain outside not from a raw love of nature but to give expression to her concern over the future of her over-sensitive grandson, I am struck by the vague memory, now, but only in a limited sense, my very own, of these images, further multiplied by the new translation and the heightened valence of the language.

I recognize it, I’ve been here—but I don’t remember it.

Were these Proust’s memories?

The book is consummated out of himself: imagination and sensation are wed under the law of anamnesis.

A reported dream, even as we report it back to ourselves upon waking, is not a dream, but a very quiet, free indirect discourse. A private language? Not at all.

But if the while I think on thee

I almost don’t believe in this more direct title, In Search of Lost Time, however much I like it. Where is its poem?

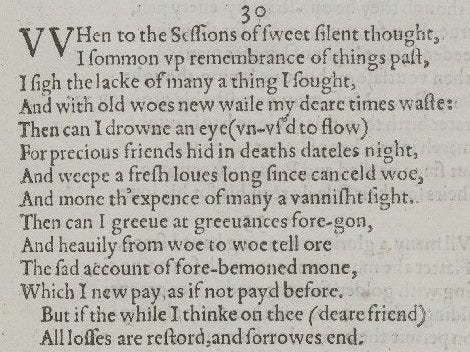

When I read Shakespeare’s 30th sonnet, from which Moncrieff took his English translation for the title for À la recherche du temps perdu, I am amazed at how perfectly it works. And it’s not just this phrase, “remembrance of things past”, that Moncrieff takes but with it also the entire poem. The phrase draws the rest of the sonnet toward the book, like a constellation of fireflies following a captured comrade, glowing in solidarity outside the transparent prison of its jar. Even the typesetting of the 1609 Quarto looks like the typesetting of the Vintage edition of Moncrieff’s translation.

“[D]eare friend[,]” in the context of the poem revivified for the title of Proust’s book, can refer to many, to the multitude of spirits inhabiting the book of his life. And yet, I cannot help but read this deare friend as spoken instead by Moncrieff alongside his lonely translation cut short by death—and why not, spoken by the reader too—to Marcel Proust, whose book of woes told over and over, like few others that I am aware of, ends all sorrows and restores every loss.

I have started In Search of Lost Time many many times over the years, only to stop a few chapters in, feeling not quite ready, although unsure what I must be ready for. This wonderful post is an occasion to remind me to begin (and quite possibly fail!) again…