On certain evenings, after a long walk through the neighborhood, I would come back to my apartment, nearly running to my desk or to the spot on the couch where I left my notebook, and I would flip through the pages of the book I was reading, or through books I had already read, usually within the last few years, in search of a pregnant word or phrase. Sometimes it would be enough to reread the sentence where I had last stopped — then I would feel nearly ill with excitement, would leave the book aside again without having advanced a single line, and would begin writing, as if in response to what I had just seen, as if it had taken my second, disconnected re-reading, emulsified in the body of the walk I just finished, in order to bring it to its full potential of significance, hovering somewhere on the page, at the clean termination of a paragraph or chapter. But these “responses” of mine were never sufficiently coherent, never quite epistolary in style, as any good response should be, and never truly critical in spirit. There was nothing academic about what I was doing, but neither was there anything fully poetic in it. I was in the narrow grips of what from outside must have looked like an aimless, stupid form of repetition and variation, an insane exercise, but which was, from my own perspective, an urgent struggle both against myself and for myself — even if it was in strong conjunction with the subjectivity and voice of another that this unfolded, again and again, on the page. If I copied, wrote, re-wrote, praised and abused a phrase, for example, out of Wittgenstein’s notebooks — the way a musician forcefully throws a note, without modulation or rhythm, into a piece he is playing in a completely different key so that the repetition functions as an exercise in the identification of unillustrative, unilluminating difference — I only did so for as long as it took me to become almost entirely disenchanted with the phrase (as well as its discordance with my own writing, however much it seemed to harmonize with my feeling), until it was like a household tool, the specific meaning and application of which I had exhausted by misuse. Then it felt like I had stolen the word or phrase for the sole, petty reason that nothing seemed so impossible as putting down the correct one myself. I take Wittgenstein’s line, for instance, dated April 18, 1915: “The subjective universe.” It is separated on both sides by white space, indicating that it was written alone on the page, away from the notes coming before and after it. But already I want to transcribe both of the other notes in their entirety, along with needless explications — I am demonstrating, without any real reason or desire, the thing I would rather only describe at some remove, namely, the uncritical and unpoetic way in which I approached fragments of text that meant something supercharged to me, usually because of their ambiguity: Thus: “The subjective universe.” Is this note meant to refer to the operations of logic? Or is it a personal remark that has nothing to do with problems of proposition and notation? I imagine it both ways until I take the note, The subjective universe, and write it at the top of a page in my own hand, deciding that it is to be the title of a book (!) that I will write in one month (!!), under the cover of night, fueled by coffee and the interventions of the holy ghost, punctuated by strange, apodictic sentences and built up out of the prose of an intense desire to flesh out a single line that I have not understood in the light and air of its own world (ingenious commentary, like Swedenborg on a line from Revelation). And the next morning THE SUBJECTIVE UNIVERSE makes as much sense to me as the outlines of the dreams from the night before, already passing away into the pleasing, if frustrating cloudiness of uninterpretability and personal insignificance.

*

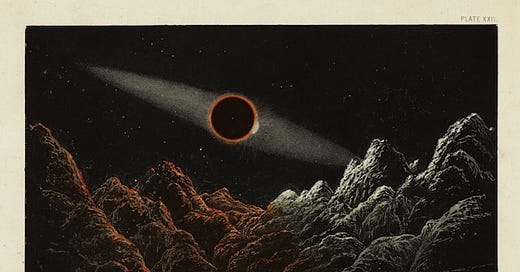

There are books you pick up that, as you begin to read, eclipse, partially or totally, all of your own thinking — which disappears behind the foreign body of the text in the same way the sun disappears behind the moon. In that momentarily suppressed, obscured atmosphere of intellectual, linguistic eclipse, the world itself cannot but look different, charged with a superstitious significance, a kind of wonderment that instills in you the desire to say something whether or not you actually know what to say — and, of course, you never really do know what to say before you speak (or, for that matter, before you write). Heinrich von Kleist, in his “On the Gradual Formation of Thoughts in the Process of Speech,”1 describes how it is to develop a thought while speaking, in this case to his sister,2 an understanding and formidable interlocutor:

Nothing in all this is more useful than some movement on the part of my sister, a movement indicating that she intends to interrupt me. For my strained mind becomes even more excited by the need to defend this inherent right to speak against attack from the outside. The mind’s abilities grow like those of the great general who is faced with a very difficult situation. [. . .]

The other person’s face is a curious source of inspiration for a person who speaks. A single glance which indicates that a half-expressed thought is already understood, bestows on us the other half of the formulation.

Isn’t a book, which at first seems to silence all thoughts of our own, something like this interlocutor who provides us with the resistance that will subsequently accelerate our thinking beyond what it could have otherwise achieved?

I will be reading any given array of books and be, as Henry Miller puts it somewhere, in “fine fettle,” reading here and writing there in a symbiotically effective, low-grade fervor — and then, I will open up a book that I have had my eye on for a long time, something that I will have worked myself up to read, and then all of a sudden (already a few pages into the book), my hand that before so easily worked out everything on the page in a seamless automatism ceases — my writing-thinking hand freezes. I am then doing whatever the opposite of thinking is. Am I digesting at that moment? I am erasing, silently and invisibly erasing.

What is vital about this intellectual eclipse, the moment of Anstoß, of stimulating resistance in the face of an interlocutor, is the moment after, when the sun of our mind along with every quotidian object into which it breathes life, light, shadow, and heat is something completely new. This moment, when you can finally write and think again after a silencing confrontation with a text (sometimes all it takes to darken the whole world is a few lines, a little stanza of poetry moving in the right trajectory), is the moment of minimal difference,3 when no single thing has changed but when the sense of the entire field, in the eye of the observer, has become irrevocably altered.

This amazing essay, worth a whole shelf of analytic philosophy, is quoted in full by Slavoj Žižek in Less Than Nothing (Verso, 2013), 570–573. Heinrich von Kleist, “On the Gradual Formation of Thoughts in the Process of Speech,” translation by Christoph Harbsmeier. (“[F]rom 1805, first published posthumously in 1878[.]”)

One can’t help but wonder what this essay would look like had Nietzsche written it; his sister also acted as interlocutor but hardly of the same apparently fine caliber as Kleist’s. Nietzsche’s nickname for his sister was “the lama”.

Described with such felicitous repetition by Slavoj Žižek, throughout his books, and such beauty by Alenka Zupančič, specifically in her book The Shortest Shadow: Nietzsche’s Philosophy of the Two. (MIT Press. 2003.)