What he searches for in books is revelation. He skims through them. Suddenly, to his great delight, a sentence... an incident... whatever... something there... At which point he proceeds to levitate toward this something with everything that he has within him, at times clinging to it as iron to magnet.

—Henri Michaux, A Certain Plume

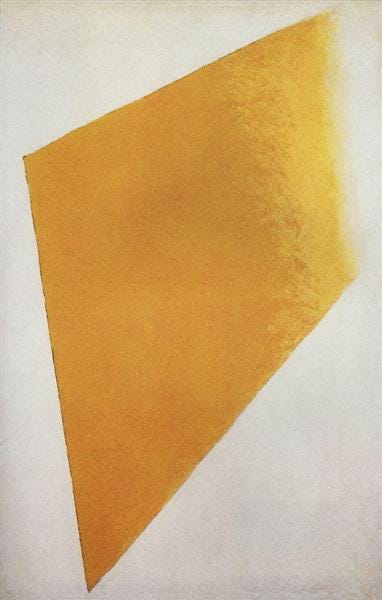

...a blissful sense of liberating non-objectivity drew me forth into a "desert", where nothing is real except feeling…

—Kazimir Malevich, “Suprematism,” Part II of The Non-Objective World

The quietest hours of one’s reading induce something like proprioceptive hallucination—that is, a warping of one’s spatio-tactile perception of one’s own bodily reality—rather than the visual or auditory kind, by way of which the eye and the ear seek, respectively, to mold the world according to their forms, while disregarding all others as unrenderable outsides. (Text, however vividly we may engage with it, does not make us literally see anything new; it does, or can, affect how we see everything else already, but this does not occur on the sight–hallucination continuum.)

Reading is done with and to the body. The text is not merely in the eye, nor even in the “brain,” but also the mouth (Tzara: “Thought is made in the mouth.”), the stomach (Nietzsche’s frequent and otherwise half-explicable comments about “digestion”), one’s hips and shoulders and fingertips. It is worth quoting Wittgenstein at some length here:

We may say that thinking is essentially the activity of operating with signs. This activity is performed by the hand, when we think by writing; by the mouth and larynx, when we think by speaking; and if we think by imagining signs or pictures, I can give you no agent that thinks. If you then say that in such cases the mind thinks, I would only draw your attention to the fact that you are using a metaphor, that here the mind is an agent in a different sense from that in which the hand can be said to be the agent in writing.

If again we talk about the locality where thinking takes place we have a right to say that this locality is the paper on which we write or the mouth which speaks.1

It is as if the flesh reached out in both reading and writing to become the word more than the word itself. Reading is not done “in the head,” as Remy de Gourmont agrees: “We write, as we feel, as we think, with our entire body.” The body resonates the thin contours of text like a diamond stylus picking up the patterns in the black groove of a record, and, consequently—rather than inducing any kind of visual–hallucinatory run-on effects—causes all manner of strange bodily, proprioceptive distortions.

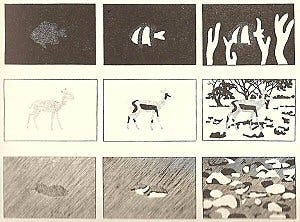

Having sat still for a while before an open book, you might feel swept up (or swept away) in the sense that your body has disappeared like the still form of a camouflaged animal against a disruptively patterned backdrop.

At such moments, you become nothing but a pair of hands, a pair of eyes, a tongue (maybe a single foot, planted on the ground), anatomically disarticulated to yourself, while all corporeal feeling holds its breath (sometimes you literally hold your breath, e.g., as you approach the bottom of a page) suspended, and the body becomes as insensate as the page. (The body becomes like a heavy suit of armor lying on the other side of the room, a blind, heavy double.)

Your hands will feel as if they have vanished even as they grip the book in front of you, and the sensation of your own face will collapse into a two dimensional plane, as if your entire head had become nothing but a compressed mouth—the surreal liquid of its tongue poured out evenly across a Malevich–style plane.

When reading the right book, one feels as if an electromagnet, sensitive only to the text at hand, had become active in one’s body: the text, then, is either like dead matter which reacts not at all, or like magnetite, valent, dynamic and attractive at all times, depending only upon that inner, sympathetic power which blindly exerts its pull.

Ludwig Wittgenstein, The Blue and Brown Books. Harper Torchbooks. 6–7.