Drawing Down the Moon

Part 3 of my review-essay on Knausgaard’s Morgenstjernen; Melancholia, Black Metal and Détournement

<Previous>

Land of light

Land of sun

Land of light

Land of sun1

The center of gravity of Knausgaard’s Morgenstjernen books is the new star that unexplainably rises into the night sky—over the fjords, over the forest, over the graveyards, churches, and summer homes, into the stultifying heat of an August night in Norway. We see it rise over and over from the myriad perspectives of characters, from nurses to schoolteachers, from undertakers to architects. Everyone tries to account for its presence, to make it provisionally consistent with the logic of their worldview; some ignore it as best they can while others’ attention is almost completely taken up by it. The star forces a kind of acute paranoia on everyone to a greater or lesser degree: the belief that there must be some controlling force, a subject, behind every phenomenon.

It is significant that the only character, to my mind, who is able to integrate the new star’s (weird) meaning (and its eerie run-on effects) into her life without issue is Tove, an artist and manic-depressive—arguably an hysteric, in the best possible (Lacanian) sense. Her interpretive powers and fierce libidinal economy are equal to the phenomenal force of the appearance of the weird, the actually new, in the form of the star.

In fact, Tove has a direct parallel in film: Justine, played by Kirsten Dunst, in Melancholia, by Lars von Trier. The main imagistic similarities are obvious: the planet Melancholia appears in the sky and moves very quickly—horrifically slowly to the human eye—toward earth, which it will annihilate. The main difference is probably just as clear: Morgenstjernen: Total life : Melancholia: Total death. (Is this really a difference? Or rather a deep similarity, defined by totalization, a pure unbalancing of the scales of life–death?)

Not despite but precisely because of these two women’s—Tove’s and Justine’s—nominal mental illness, they become the only resolute moral actors in their respective situations: imminent world-destruction, the certainty of total death in Melancholia and the creeping possibility of the horrifying disappearance of death altogether (the opening of the gates of the realm of the dead) in Morgenstjernen. Because of her hitherto crippling depression (due to anything but the incoming planet), Justine becomes the only person to take responsibility for the comforting of a child in the face of certain and total death.

Tove, because of her near-schizoid facility for emotion and representation, is able to take the radically new appearance of the star, as well as frightening Satanic visions, in stride while everyone else lives on in deferred panic and denial.

If the star, as I said, is the center of gravity for the plot (and non-plot), the rising and falling leitmotif is the nature-laden, amoral, darkly glowing imagery and violence of Scandinavian black metal.

Take some phrases from the opening of The Third Realm (spoken no less by Tove):

They say that depression is concealed anger. I think of it as a petrified troll. A creature of darkness and the incomplete—irate, dangerous—transformed by daylight into something unmoving and lifeless.

[. . .]

The folk tales.

The trolls, the three doors, the forest. The one where the animals can talk, and people turn into animals. The one with witches, crofters, kings, underground halls, tree stumps, princesses no one can spellbind, stepmothers and poor women, mountain pastures and rugged blue peaks.2

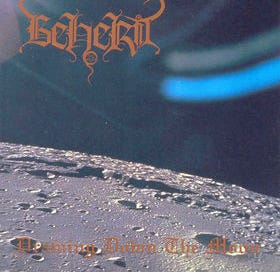

And from “The Gate of Nanna” by Finnish black metal band Beherit:

The dream descends to the region of moon

To the land, the sphere of eternal sin

A half light, dark the realm of Nanna

The realm of spirits and the father of the gods

Oh, shine of moon, of the astral gods

It ravishes, it calls us to sin...

The lyrical affinity glares like the eyeshine of an animal.

In a brief passage of phone dialogue, Knausgaard has two characters go over a quick history of black metal in Scandinavia (clearly intended for the reader unfamiliar with the genre). He does a fine job showing that black metal shared the ethos, if not the pathos, of punk rock in the Anglo-sphere: a general spirit of opposition, an assertion of power through hardness and speed. But whereas punk rock was essentially left-liberatory in the neoliberal-conservative countries of Britain and the US, black metal assumed (in the first and second waves) a largely right-wing authoritarian and explicitly evil political position in the famously more social-democratic-leaning Scandinavia.

Take Euronymous—guitarist for Mayhem and founder of Deathlike Silence Productions, murdered in 1993 by at-the-time bandmate Varg Vikernes—and his almost comical explanation of his support for communist countries: “he was a member of the Norwegian [Marxist-Leninist] communist youth group Rød Ungdom[,]” which he left “allegedly because he came to realise that they were ‘just a bunch of humanists’. He said ‘as I hate people I don't want them to have a good time, I'd like to see them rot under communist dictatorship’.”

And then there is Euronymous’ murderer and arguably the most characteristic and controversial Norwegian black metal artist, Varg Vikernes, with his explicitly mystical-fascist politics.

Knausgaard forms a composite of bands like Mayhem, Burzum, Beherit, Abruptum, et. al., in the fictional band Domen, who does not record albums but only circulates demos among friends; who does not tour but plays secret generator shows in the woods; who has vaguely anti-capitalist sensibilities, but which are ultimately vulnerable, for all their unclarity, to recuperation. The band’s frontman is Valdemar, a further composite of iconic black metal personalities. The looks and charisma (sic) of Dead, the “Norse” fetishizations of Vikernes and the vocals (or so the descriptions lead me to imagine) of Nuclear Holocausto Vengeance.

The characterization of black metal in Morgenstjernen, but mostly The Third Realm, is Knausgaard’s signature move of bringing out a political/social taboo and foregrounding it for further literary inquiry. In My Struggle, he did this with his 400-page essay on Hitler and Mein Kampf. Here, he is doing it with a genre of music that is professedly evil in every way—but to stronger fictional effect.

This also brings up a minor point of translation: the original Norwegian title of The Third Realm is Det tredje riket, or, more literally rendered, The Third Reich.

This necromancing of taboo subjects (murder, insanity, sadomasochistic sex, infidelity, just to name a few) in the cultish scariness of fascist symbolism is softened in the translation of the book as The Third Realm. This would almost be like translating the title of Knausgaard’s notorious autobiographical novel Min Kamp as My War—it is correct but nullifies the controversial hijacking of a foreboding phraseology that the correct translation, My Struggle, uncomfortably forces on the reader. (The main justification for not doing this with The Third Realm is thematic continuity, The First Realm and The Second Realm both being periods of Biblical history theologically presented in A Time for Everything, as mentioned here.)

I very clearly remember seeing My Struggle in bookstores when I was younger, knowing nothing about it, and thinking, “Jesus Christ, why would you name your autobiographical novel that.” —and I thought so along with everyone else, which is why it’s such a good title.

This same effect is largely lost today in one of the most successful cases of détournement I can think of: the band Warsaw changing its name to Joy Division, the nickname of the Wehrmacht’s sexual slavery units.

I say this is a “successful” case of détournement because it is not a case of irony that reifies or recuperates what it steals from but an actual direct theft of the sign. This is the difference between actual hijacking and unwitting influence. It is not clear that the name Joy Division is ironic at all, only that its significance has been realigned entirely, to the extent that, when you say “Joy Division”, everybody already knows what you’re talking about.

Further recommended reading on Black Metal by Neo-Passéism. It’s fun, catty and I love the art, as with all their pieces.

From “Summerlands,” by Beherit.

Karl Ove Knausgård, The Third Realm, Trans. Martin Aitken (Penguin, 2024), 3.