These sketches—Drifts—are discontinuous and do not need to be read in chronological order.

In a drift [the most direct translation of the French dérive] one or more persons during a certain period drop their relations, their work and leisure activities, and all their other usual motives for movement and action, and let themselves be drawn by the attractions of the terrain and the encounters they find there. Chance is a less important factor in this activity than one might think[.]1

Laszlo Krasznahorkai’s books are long hunts: his clauses are the footsteps; his periods are gunshots, and by the end of a novel or a series of shorter pieces (not really stories and not really essays), we are left with our ears ringing, standing in a bloody, silent forest.

Writing like Knut Hamsun’s, which, though roaring with fantasy, carries constant whispers of his life; and writing like Henry Miller’s, which is ostensibly autobiographical, though fiction pulses through every moment of it, like sodium pentothal through the blood of a would-be liar—dialectical autobiography.

For me, Powys is an eminently cross-sectional writer (a point I address here and here somewhat). When I read his books, I don’t read his books. I only ever read Powys under the sign of one of his books, and these revolve overhead like constellations. The first 100 pages of one book, the first 100 of another, and the first 80 of a third, discontinuously coming in and out of sight like parades of creatures in a magic lantern show. And to return to the first metaphor: the fact that these constellations come around only every few years shows that their orbits are elliptical and that they live at unimaginable distances, and so must burn very brightly for me to see them at all during the periapsis (the point in the orbit closest to the attracting body).

There are writers who haunt. The first contact is surprising and unpleasant, but once such presences are understood as possible, further encounters are sought out. Here, I see Clarice Lispector, as though hovering in the doorway.

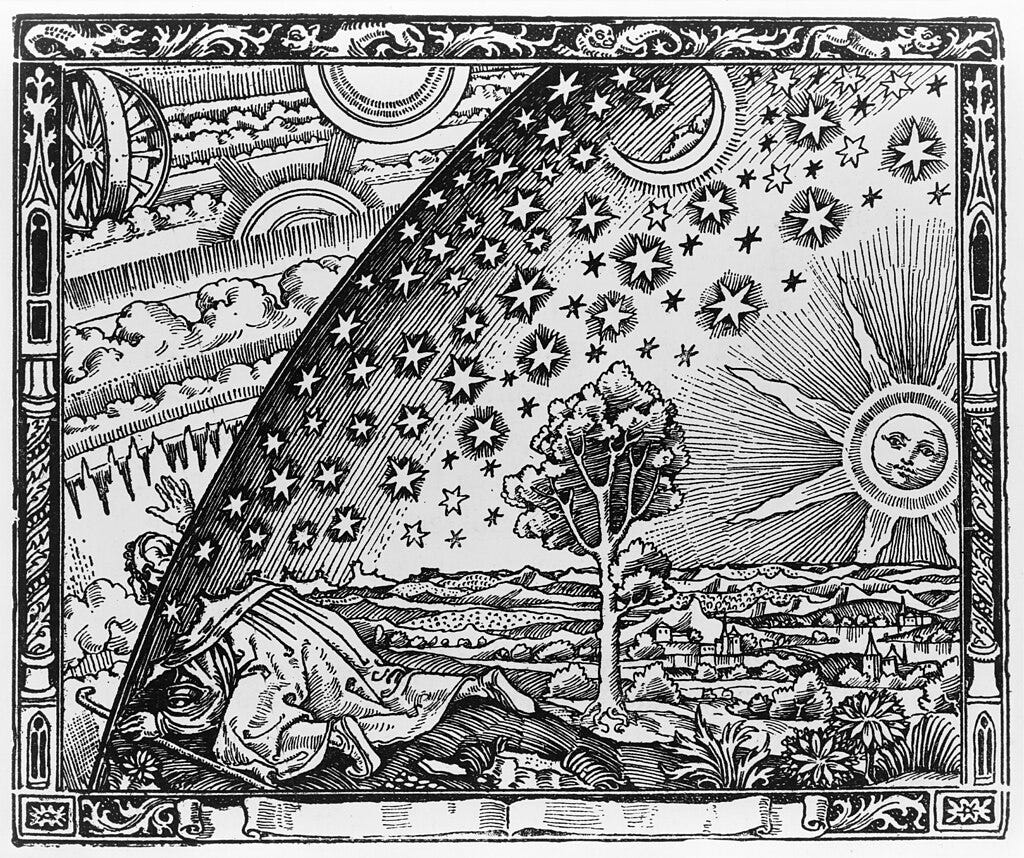

Sometimes, when we stop reading a book, all we do is stop reading. But other times, we stop, mark our spot, put it away on a shelf or under our bed, and though we go on reading something else we end up doing so as an intermittence, a parenthetical, an extended footnote to the text we left off with previously. This has been my experience with Robert Burton’s The Anatomy of Melancholy. About a third of the way through it, everything I read (present tense) takes place in the scholastic, proto-hypertextual and ebullient 16th/17th-century world of Burton. And some day, when I do finish The Anatomy, I will have to reread all those years worth of books that it enclosed, like the outer sphere of firmament in the famous Flammarion engraving.

Hermann Hesse said of Robert Walser: “If he had one hundred thousand readers, the world would be a better place.” Who can say if this is true: Walser surely has been read by more than 100,000 people, and yet—. People should read Walser, as well as writers like Giono, Hesse and Mann. And then, there are also people who need, much more than the kindness of Giono and Walser, voices of eloquent, capable violence: Unamuno, Benjamin, Cendrars, etc.

What I often find myself on the lookout for is the feeling that, in reading something, I am getting up to no good. A negative example: When I read Infinite Jest, I never came close to this feeling of “getting up to no good.” The first 300 pages, I enjoyed (I liked the footnotes). But after a while, I felt that the book was only an exercise, a big tune-up for the real thing that was always only still to come. By around page 800, I wanted to read something that would put any kind of taste back into my mouth. I had gotten sick of Wallace's clean nexus vocabulary: dentition, strabismic, anhedonia—and this one really bothered me—spectation. Over and over again, spectation. When I finished it, I reread some passages of Maldoror, which functions like an antidote to that peculiar strain of lexical cleanliness.

The translation of Guy Debord’s “dérive” as “drift” is my own.