The unreality of games gives notice that reality is not yet real.1

A good old-fashioned fake

The holidays suspend work, obligations to regularity, and, maybe for a moment, the general spuriousness of everyday life. At times, even the most crass, commercial consumerism is nullified to reveal something of the spirit of gift-giving, as opposed to mere exchange, on these days. In the fake vinyl Christmas villages built up in the squares and parks of major western cities in the weeks preceding Christmas, a little can still be found—a glimmer, and if only out of the edge of one’s vision—of the medieval market, of a town concentrating itself against the long cold, of a unified, sabbath-like behavior that dignifies even those who bemoan their involvement in it: use over exchange, if only apparently.

The feeling of time,2 leading up to and including Christmas day, almost seems to expand in an all-too provisional annihilation of time by space.3

The overt falsity of Christmas is its best quality. The person that sees in Christmas nothing but the hyper-commodification of life misses the point: that is how everything already is anyway. The high artifice of Christmas is not like a veil being lifted that lets us see how commodities “really are” —it is a further veiling, a doubling, that for a few days gives the commodity form something like an identifiable body, like a specter who, on one special day out of the year, reveals itself by its glowing garments. In a world held in thrall to the virtual (and bone-headed representations of virtuality meant to be taken for the virtual itself), good old-fashioned falsity becomes more and more refreshing; it lets us feel that we might find, behind the unnatural, warmly glowing lights, the plastic or real tree obscuring the window that looks out on the street, and the garlands and tinsel covering downtown, once these have been removed with the coming of the new year, a world that is real, that is ruled by the simple, undialectical opposition between mere fakery and mere reality. For a few weeks, a few days, we hover at a standstill in an enchanting illusion.

Surplus representation and longing

There is something heartbreaking about fake things made to represent their bygone—or prohibitively scarce and expensive—originals. The electric space heater, e.g., carefully made to look like a wood burning stove represents not only the actual wood burning stove, only very rarely found in homes today, but also, even much more so, the longing for such obsolete and carefully designed centers of life. The actual wood burning stove is an anachronism (which speaks for an appreciation of the past), but the surplus representation of its fake counterpart signifies a nameless, longing melancholy (nameless because it resists the language of medicalizing compartmentalization) so strong that it would be almost impossible to sympathize with if we were not already being forced into a position of constant empathy with it, which takes its refuge in the mindlessly gentle contours of fabrication. These contours of representation, two-orders removed and nearly convincing, would ask our forgiveness could they speak, and, full of a strange pity, we would offer it the plastic tear rolling down our cheeks.

Concentration

The naivete of false objects, like the tinsel Christmas tree and the drifts of paper snow at its feet, suggests to us in quiet moments that behind them lies a true (if harsh) world, a world not diffusely pervaded with the falsity that for a wonderful moment concentrates itself before us in the pleasing forms of wooden elves, toy train-tracks that lead nowhere, and illuminated miniature villages on living-room shelves, as though we had caught, like rare fireflies, the escaped elements of a magical diorama.

Inoperativity/Stillstellung

The false, fakery, facsimile, the facade: these are so endearing to us because, for all the care that goes into making them convincing as representations, they are never able to shake off the aura, or halo, of ineffectiveness (or inoperativity) that grounds them and protects them against the killing current of reality—the endlessly flowing voltage of effective phantasms, autonomous virtuality, and the inhuman music of the death machine (variously called: on-demand production, the free market, “the economy,” et. al.). Of toys, e.g., Adorno says:

The little trucks travel nowhere and the tiny barrels on them are empty; yet they remain true to their destiny by not performing, not participating in the process of abstraction that levels down that destiny, but instead abides as allegories or what they are specifically for. Scattered, it is true, but not ensnared, they wait to see whether society will finally remove the social stigma on them; whether that vital process between men and things, praxis, will cease to be practical.4

The meaning of toys, those little ur-objects and talismans of Christmas, is highly ambiguous.

Ambiguity is the manifest imaging of dialectic, the law of dialectics at a standstill.5

The Star of Bethlehem

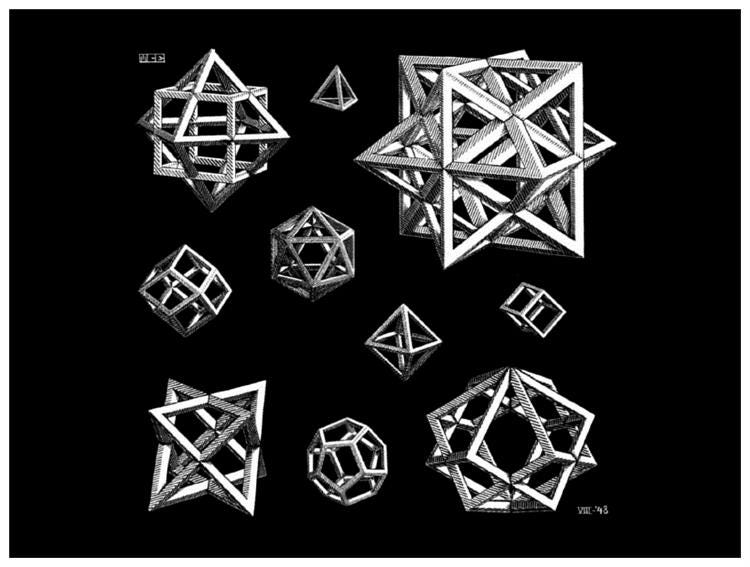

[. . .] Escher’s paintings depend upon unsettling rather than ignoring the rules of perspective.6

The child’s nightlight, and not even the shadow lantern from the very first pages of Remembrance of Things Past, but just a simple plug-in light in the molded shape of a seashell, an angel, a star, a moon, or a light-conductive, glowing bunch of flowers: these keep cats and dogs company, installed low down on the wall as if for them alone, in the quiet, free hours of the home when everything and everyone sleeps. The shadows they cast are few and move along the corners and edges of walls like silent marine creatures under the surface of a hidden pond.

The nightlight is the star at the top of the Christmas tree drawn down—as in some absent pentagrammatic ritual—into the inoperative world of preserved life, the nightlife of children and animals.

The child who cannot sleep and the dog who has slept all day long, and so stays downstairs by the dark obelisk of the front door, combine their small forms in the shy glow of the nightlight; their mute nighttime worlds overlap in this most touching crystallization of artificial illumination. The child goes to the kitchen for a glass of water and the dog follows, but not at all like it follows the mother and the father when they get home, the genial or dismissive masters of reality, of real life. The child and the dog, in the weak illumination, come into their own as equals, as in some fairy tale, and their respective complicity with and subjugation to the adult world of lights that only expose (rather than enchant) sleeps soundly too. They become their own medieval-surreal cutouts, casting shadows like Proust’s magic lantern into their world. And if the lights on the tree have been left on, it is all the better. Even from outside on the freezing street, its useless halation can be seen. The child goes back up to bed and the dog returns to its watch, and if you see him looking out of the window in the red, green and white light, a chill moves you because, though it is only an animal gaze, that of some family pet, the light and air of exceptional falsity guarded over by a dog makes things seem unbearably strange, as if anything were possible, and it is almost like you were standing at some kind of gate, waiting for it to close so you could finally break in.

Theodor Adorno, Minima Moralia, Verso Books, 2020. §146.

Momentarily inverting Marx’s notion of time–space compression, the “annihilation of space by time.”

Again, provisionally and apparently, in the home or the “interior,” quite because of what occurs “outside,” in the distant, invisible chain of production running always elsewhere— kept out of view like the taboo of death—at white-hot speed.

Ibid.

Walter Benjamin, “Paris, the Capital of the Nineteenth Century,” [Exposé of 1935], in The Arcades Project, Trans. Howard Eiland and Kevin McLaughlin, Harvard University Press, 1999. 10.

Mark Fisher, “The Lost Unconscious: Christopher Nolan’s Inception,” Ghosts of My Life, Zero Books, 2013. 209.