<Previous>

[analogy] makes possible the marvellous confrontation of resemblances across space[.] — Michel Foucault, The Order of Things

In another piece, I called Powys a cross-sectional writer. What I should have said is that his books turn me into a cross-sectional reader.

I always begin Powys’ books with an interest fired by novelty and fast enjoyment. His prose is a magical, parapsychological whirl of exteriorized interiority and character description that verges on stippling. What is inside a character rapidly becomes outside. A thought follows a line of flight and becomes its surroundings. A subjective feeling merges with the weather. The opposite occurs too. Atmospheric effects and the setting—the Welsh countryside of the early 15th Century, the roads of Glastonbury and Dorset—reach inside their inhabitants as though by a bright, emotional osmosis.

Everything is connected in Powys’ books. If the reader saw these connections from any perspective other than the shifting, 3rd person narrator, the effect would be one of a gorgeous, historically inflected paranoid schizophrenia. But because we see the events and connections from slightly higher up (Powys’ narrative seems to take place from the height of a thatched roof cottage, not too high but certainly not eye level with his characters, who always seem slightly far away) the logic of this interconnectedness reminds me of the four similitudes of the medieval (or pre-classical) period, as outlined by Michel Foucault in The Order of Things.

Foucault opens his discussion on the medieval mode of knowledge, or episteme:

Up to the end of the sixteenth century, resemblance played a constructive role in the knowledge of Western culture. It was resemblance that largely guided exegesis and the interpretation of texts; it was resemblance that organized the play of symbols, made possible knowledge of things visible and invisible, and controlled the art of representing them. The universe was folded in upon itself: the earth echoing the sky, faces seeing themselves reflected in the stars, and plants holding within their stems the secrets that were of use to man. Painting imitated space. And representation—whether in the service of pleasure or of knowledge—was posited as a form of repetition: the theatre of life or the mirror of nature, that was the claim made by all language, its manner of declaring its existence and of formulating its right of speech.1

This could just as well describe (with limitations, as we will see) the style of Powys, which famously strikes contemporary readers as bizarre or foreign, as if its concerns were of another time altogether. The voice of the text is urgent—but why is not always clear to the reader, especially if they want to see the development of anything like a traditional plot.

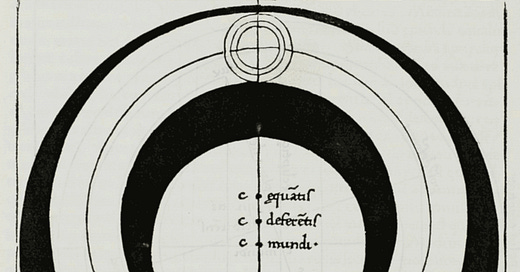

Foucault delineates four essential moments—similitudes, or forms of affinity that shine with significance—in the medieval period’s extremely rich “semantic web of resemblance,” through which every aspect of the world articulates itself. This chapter, “The Prose of the World”, contains some of my favorite lines from the book.

It’s worth including a few highlighted extracts as well as how they illuminate the strange case of John Cowper Powys.2

The four similitudes

convenientia

Those things are “convenient” which come sufficiently close to one another to be in juxtaposition; their edges touch, their fringes intermingle, the extremity of the one also denotes the beginning of the other. In this way, movement, influences, passions, and properties too, are communicated. So that in this hinge between two things a resemblance appears.3

Convenientia is the ruling similitude of Powys’ characters in any given scene. They hinge on one another, their psyches and affective capacities intermingle through physical proximity—the souls of the men, women, children, animals, plants convene into one another (to attempt an alternate translation of the word). There is a syntactic comparison to be made here; each character acts upon those near to it in space like words upon each other in a single sentence.

aemulatio

The second form of similitude is aemulatio: a sort of “convenience” that has been freed from the law of place and is able to function, without motion, from a distance. Rather as though the spatial collusion of convenientia had been broken, so that the links of the chain, no longer connected, reproduced their circles at a distance from one another in accordance with a resemblance that needs no contact.4

If there is something syntactical, sentence-bound, about convenientia, then aemulatio functions through characters on the level of greater grammar. Aemulatio is paradigmatic. It is the resemblance and connection of characters with their family, their loves, their hatreds, and all the convenings with other personalities out of the past.

analogy

In this analogy, convenientia and aemulatio are superimposed. Like the latter, it makes possible the marvellous confrontation of resemblances across space; but it also speaks, like the former, of adjacencies, of bonds and joints. [. . .] [analogy] can extend, from a single given point, to an endless number of relationships. For example, the relation of the stars to the sky in which they shine may also be found: between plants and the earth, between living beings and the globe they inhabit, between minerals such as diamonds and the rocks in which they are buried, between sense organs and the face they animate, between skin moles and the body of which they are the secret marks.5

The high point of Powys’ writing resides with analogy in precisely this sense. Powys breaks open the difference between living and dead, biotic and abiotic, past and present, present and future, treating such oppositions as false, indeed, as completely arbitrary and crudely scientistic (as opposed to scientific). If the way characters behave in his novels is strange—and they do behave very strangely—it is because everything is a character for Powys’ fiery oratory of storytelling.

The door of an old family home, a tree planted at the side of a garden path, the youthful eyes of a priest, the hair and hips and hands of a beautiful woman, the teeth and gait of an old man, his old hat and cane, the birds arcing over a lake whose deeply glowing water is at once ancient and ever self-renewing: all of these are imbued with individual, vying souls, with highly particular but typologically determined personalities of their own.

sympathies

Sympathy plays through the depths of the universe in a free state. It can traverse the vastest spaces in an instant: it falls like a thunderbolt from the distant planet upon the man ruled by that planet; on the other hand, it can be brought into being by a simple contact—as with those “mourning roses that have been used at obsequies” which, simply from their former adjacency with death, will render all persons who smell them “sad and moribund”.6

The included opposite of sympathy is antipathy. For Foucault, this pair gives rise to and includes the three prior similitudes.

“Sympathy” marks the twilight of Powys’ writing. This fully sympathetic quality is what Powys’ is always looking and reaching toward but which, as far as I can tell, he never fully attains. When I read the above, I think of Marcel Proust7—but Powys, tragically and comically, with great skill and furious activity, never fully enters into this sphere of “sympathies”. He remains exiled in the spheres of analogy, aemulatio and convenientia. His books seem like highly detailed rituals by which he tries to conjure the “depths of the universe in a free state”, always producing something else, some lesser demon, by accident.

This exile (possibly a self-exile) at the dimensions of analogy, aemulatio and convenientia is, however, a fascinating quality in itself. It’s fundamental, “unsympathetic” (only in the above sense) striving is what makes me return to his strange books with cross-sectional fits and starts, reading 100 pages of a book here, 80 pages of another there.

I read his books in a similar way to how I imagine people use decks of Tarot cards—not by going through the deck in a linear way, which would efface all meaning, excitement and surprise, but by jumping in and out, forgetting, reacquainting oneself with the imagery and seeing how it weaves into the other cards, or the other books, in a fun, discontinuous experience of reading that passes away as quickly as it begins.

For now, this is the fourth and last piece dealing with John Cowper Powys. Follow the “Previous” link above to retrace the installments if you haven’t already read them: they’re somehow the most popular pieces on COM-POSIT.

Michel Foucault, The Order of Things: An Archaeology of the Human Sciences, Vintage Books, 1994. 17.

If you’re interested in reading the relevant section unabridged, here is a PDF of the edition I am using.

Ibid., 18.

Ibid., 19.

Ibid., 21.

Ibid., 23.

And many others, but Proust most startlingly represents this attainment.